EXCERPT:

Everything We Thought Was Beautiful: Interviews with Radical Palestinian Women, edited by Shoal Collective. PM Press, 2024. 200 pp.

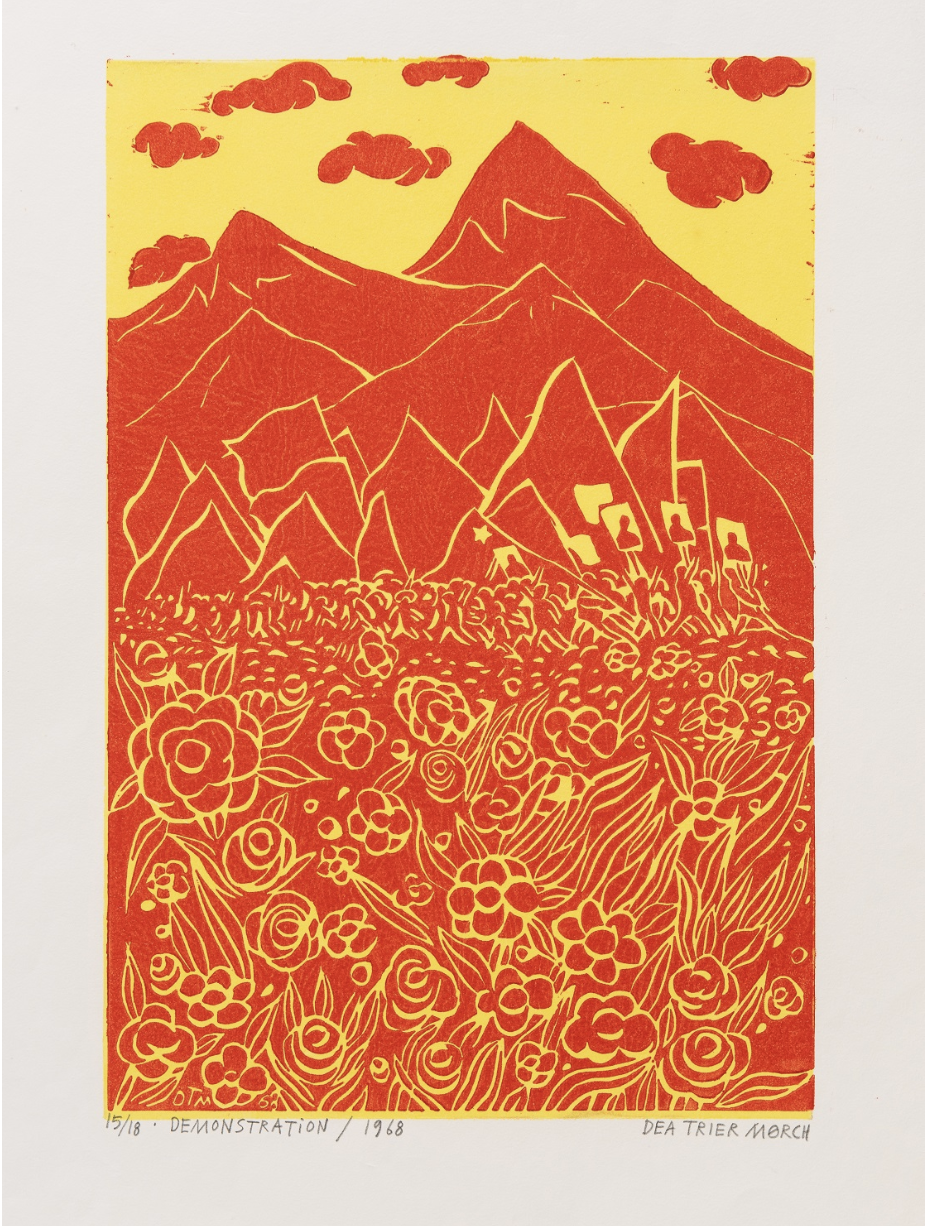

"Demonstration," 1968 –– Dea Trier Mørch

The following is an excerpt from Everything We Thought Was Beautiful: Interviews with Radical Palestinian Women, which came out with PM Press in December 2025 and was compiled by Shoal Collective.

The Amenia Free Review’s namesake hamlet is located in Dutchess County, New York, a region known for its farmer’s markets, produce, and CSAs, and where the trend is is undeniably toward a localist ethic, often admirably expressed along the lines of getting to know your local farmer. The excerpt below is an interview with Ghada Hamdan, who works on a permaculture farm in the West Bank. In it, she discusses co-ops, ecological movements, Western NGOs, BDS, and feminism, and I hope it will be read in the AFR with an eye toward what such interests— in food systems, in ecology, in land —might mean on a global scale, especially when practiced amidst ongoing genocide. I also hope you'll check out the book, a mighty testament to what is being brutally destroyed and to the bravery that cannot be.

As of December 30, 2025, Om Sleiman’s farmers are still harvesting.

-C.R.

—— ——

Ghada Hamdan

Ghada Hamdan (a pseudonym) is from Bil'in. She currently lives on Om Sleiman, a permaculture farm established in the village of Bil'in in the West Bank. The farm is situated on a piece of land that has been the subject of years of struggle. It lies close to the Israeli colony of Modi'in Illit, in ‘Area C', meaning that the land is under full Israeli control. Palestinian farmers of Om Sleiman are forbidden from building any structures, including wells. We interviewed Ghada in July 2018 in Nablus.

Can you tell us about why you chose to be involved in land-based organising?

I choose farming as a form of activism and resistance, especially agroecology because it gives you tools to have control over your resources and to be independent and self-reliant. I'm really interested in self-sufficiency because that's what we really need in Palestine. Palestinians are occupied and thus our resources are occupied. Over the years our electricity, water, and food has come from our occupier, Israel. Israel controls everything; we don't even have an independent economy of our own and this creates a population who are unable to achieve independence. We have to learn to be independent, self-sufficient, to harvest our own water, grow our crops, and save our seeds.

There was a big movement aimed at building self-sufficiency and autonomy during the First Intifada. Has the situation changed now?

The structures of our neighbourhoods in the First Intifada were different. Back then people lived in small organised communities and everyone knew each other and wanted to support each other and would know what each community member could offer. You had the farmer, the cheese maker, the people who did maintenance, the teacher, the healer. the healer. People needed each other.

Now the sense of community and voluntary work has changed due to the difficult circumstances Palestinians live under. People are more concerned with their own personal needs and now in the cities people don't necessarily know who their neighbour is. This is especially the case in Ramallah and in Jerusalem. The young generation is moving away from the villages where agricultural land is, looking for better opportunities. Nevertheless we are seeing collectives and movements who are working towards building resilient communities and supporting each other when needed. For example, more farmers' markets have started to support farmers to sell their products, and consumers are more aware about the origin of the products they buy.

Are co-operatives politically significant for you?

Definitely. I think that any groups who share similar needs or objectives can come together and have stronger influence and share the risk and financial burden of starting a project, as well as provide emotional support to each other in times of need. But it has to be done very carefully. I have seen many co-operatives fall apart because of social clashes or personal interest, or because of the lack of self-organisation. The villages used to be a good [co-operative] system; for example, a villager would have a field of corn and people would help and share the food. There was a more voluntary way of living. Now we have moved a bit from these terms and way of living together.

How strong are ecological movements in Palestine?

'Ecological movement' as a term doesn't really exist. I would say people are more aware of the environment and ecology, but to be honest it is also a privilege here to be concerned with ecology. Ecological farms and agroecology nevertheless are growing stronger and that is not related to privilege. Palestine has historically been a fertile land with peasants growing food for their own households, so it is not something new to us and not a trend. Taking in consideration the lack of support, especially financially, for new co-operative projects, and the challenges that come with starting movements or start-ups in an occupied place, I would say that there is a strong movement, especially in small-scale farming.

The system has created a comfortable bubble. It's created a situation where it's difficult to imagine an alternative way of living. It's a system that makes you want to stay inside it, even it you hate it. You are in the office 8.00am till 4.00pm, and go out at the weekend, and repeat. One of the hardest things is to get out of your comfort zone and head towards an alternative way of life. If you're producing your awn food, that's already an alternative. If you quit your job, that's an alternative. If you make your own vinegar, oil, or cheese, that's an alternative. If you build your house from mud [a traditional Palestinian building style], that's an alternative.

The language we speak has to be different. We take language for granted. But I think language is an important tool to attract people to participate in something bigger. In the last few years NGOs have really spread here in Palestine and have brought their own language. Words like 'development' and 'strategic. They're using language brought from the outside and the language is also occupying us and taking us away from our own language and vocabulary. Even people who don't speak English know what these NGO words mean.

Can you explain your critique of the word 'development'?

I don't like the word 'development' because it makes me feel that the third world countries are poor, ignorant, and backwards, that we need to work to catch up with the developed countries, 'the Western world' These terms are forced upon us from the West and they were brought to us through international organisations who come with their agendas and opinions about us. They call us undeveloped countries. But we have a different way of living and culture. The way they talk about gender, violence, poverty, women. People coming with infrastructure projects and putting a sign up saying 'USAID': that's not developing. It's the opposite. But the funders won't fund a project if they can't put up their sign and their flag.

Can you talk more about the effect of Western NGOs on Palestinian society, and on farmers?

Working for an NGO is considered to be a good middle-class job. But if these NGOs are dependent on Western funds, they are normally funded by Western governments. Your project starts to depend on the agendas of these Western organisations, because most of it is conditional funding. Depending on international funds is first of all risky because it changes all the time depending on the priorities and crises that these international organisations are looking to support. If we accept funds even from governments that condemn us and our right to resist, and consider us terrorists, how can we change the reality and the power equation we are suffering from, so that the oppressed and the oppressor are equal?

USAID [the United States Agency for International Development] gave Palestinian farmers a new kind of cucumber. The small ones. They said, 'Here's the seeds, you don't have to pay anything.’ The farmers tried it for the first season. The next year they said, 'You have to pay for the pesticide.’ The following year they said that ‘you have to pay for everything yourselves.' By this time the farmers were in so much debt, and the soil was not productive anymore. When everyone plants the same crop, that means they won't be able to sell it. In some cases [these USAID projects] have been done in collaboration with the Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture.

A similar thing happened [when Israel started occupying the West Bank] in 1967. Israel announced that all the resources of this land belong to the [Israel]l state, and they went to the Palestinian farmers and gave them seeds and chemicals and told them how to plant things. That's a way to control food, and also to gain control of our knowledge. Back then Palestinians were producing 80 percent of our needs and we were exporting sesame. Now we're importing almost all grains and legumes. What the Palestinian Authority spends on agriculture is less than 3 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP)-it's nothing.

What is your position on accepting funding at Om Sleiman?

The farm started with a 'no fund' policy for the first three years, following that we decided to accept funds from local organisations, without conditions, to fund projects and education programmes. I think that when it comes to funds it's not black or white. The owner of the land gave us the land for free, isn't that some sort of funding? When we had an accident at the farm and lost all of our seed stock, we were able to recover our costs in a week because the community helped us right away, isn't it a sort of community fund? We see the importance of having the production side of the farm as self-sufficient, meaning that the membership fees paid by our customers for the price of vegetables should cover the cost of producing these crops. But other projects that we do could have a great effect on our nature and society. Why say no to individuals who want to donate to a project they feel proud of?

There are now more small farms [like Om Sleiman] and we try to share our skills because the others aren’t organic or natural. They come and ask questions and see the results of our work. Maybe they will consider it when they go back to their farms.

We don't accept any type of funds that are conditioning us from doing what we believe we should do, also we feel it's important to not depend in any way on these sources of funding.

What is your financial model at Om Sleiman?

We are a community-supported agriculture farm, meaning that people sign up for the whole season, usually three months. They pay in advance in exchange for a weekly basket of our fresh organic produce. There is a direct relationship between consumers and us. We don't have to worry about marketing our produce, or getting money before we start the season. What members pay for is how much it costs us to grow. It might not be affordable for some people but we offer discounts and you can come and volunteer in exchange for produce as well. Having said that, I must share that producing vegetables is never enough to cover the costs of the farm, but we are not raising the prices because we want to be inclusive. What we try to do instead is to have other ways to increase our income through workshops, courses, selling dry herbs, etc.

What do you think of the international Boycott Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement?

I support the boycott movement, especially to influence the people abroad. One of the reasons why Israel is able to continue its occupation and brutality is because it is never held accountable for all the crimes it commits against us, even by international organisations whose job is to hold these regimes accountable and protect the rights of humans. Israel is mostly treated as if it's a normal country. If Israel is held accountable, things will be different. I support BDS but it shouldn't be the only way to resist, we should be able to resist in all the ways we choose.

What do you think about the factory farming of animals in Palestine?

Traditionally, people in Palestinian villages kept animals. But I don't think people are aware [of the realities] of factory farms: they imagine chickens running around freely. It's not like people visit the farms and see the thousands of chickens on top of each other. I don't think people make a connection between what they eat and the creature. When they order chicken, it's just meat. They don't think about the living creature who had a life span. But recently some consumers have started to be aware about the reality of where their food comes from. There is more and more demand for 'Baladi Eggs'- heirloom chicken eggs-and for [local] dairy products. I don't think the supply is enough and I don't think people really know what the animals they eat have been injected with.

Do you think people in Palestine have a strong connection to the land?

Of course, you try to take land from any group of people and they will hold tight to it and defend it with everything. We have a strong connection with the land because our land is occupied, because our land supplies us with everything we need, because we are a peasant community. I think the older generation, who worked on the land every day, know how precious it is and might appreciate it more.

Some people are trying to preserve the Palestinian natural heritage, like Vivien Sansour, she has a seed library and is very active in saving seeds and giving them to farmers. 1

Later generations never worked on the land in the same way. I don't think you can love your land if you're neglecting it or using chemicals on it. The younger generation has other interests, especially those who grew up in the city with no chances to harvest or plant, and those growing up in villages are sent to universities to get a certificate and have a career. [There is a culture here that] even if you have no idea about what you want to learn, you go to university, graduate, get la master', get married, have children. Most of the time you're told what to do by your parents, teachers, bosses. It's really hard to get out of this prison. I think it's applicable all over the world. It's really hard to get out of traditions, and you have to please everyone all the time. I know many people who are living a life that they have never chosen because they want to please people, or because they were too scared to try anything different.

Can you tell us about feminism in Palestine?

Here we have feminist women who don't even know they're feminist. Northwest of Ramallah there is a village called Deir Ballut. It has nine hundred dunams of land, managed by the women of the village. 2 It's all run by women. They plant, they weed, they seed, they harvest. For me this is feminist. Most of the men of the village go to work in the settlements and the women have to be responsible for covering the needs of their families.

The most vulnerable in society are those most affected by the different forms of restrictions and violence. Women, for example, face multilayered oppression starting from the patriarchal family construct until the dominating Israeli occupation. Palestinian women have always played a leading role, from resisting oppression through armed struggle to tending fields abandoned by men who left to earn an income working for Israelis. There is a misrepresentation and misperception of Arab and Muslim women by the West-they are seen as stripped from political participation but in reality they are political subjects. I invite you to see feminism in a different lens— the lens of a revolutionary Arab feminist, because in reality it's more radical than most white feminism.

- Vivien Sansour is the founder of the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library. Her website states: The Palestine Heirloom Seed Library (PHSL) is an attempt to recover these ancient seeds and their stories and put them back into people's hands. The PHSL is an interactive art and agriculture project that aims to provide a conversation for people to exchange seeds and knowledge, and to tell the stories of food and agriculture that may have been buried away and waiting to sprout like a seed. It is also a place where visitors may feel inspired by the seed as a subversive rebel, of and for the people, traveling across borders and checkpoints to defy the violence of the landscape while reclaiming life and presence. ↩

- A dunam, also known as a donum or dunum, was the Ottoman unit of land equivalent to the English acre, representing the amount of land that could be ploughed by a team of oxen in a day. ↩