JAMESON'S LEXICON:

on Mimesis, Expression, Construction

Alex Lanz

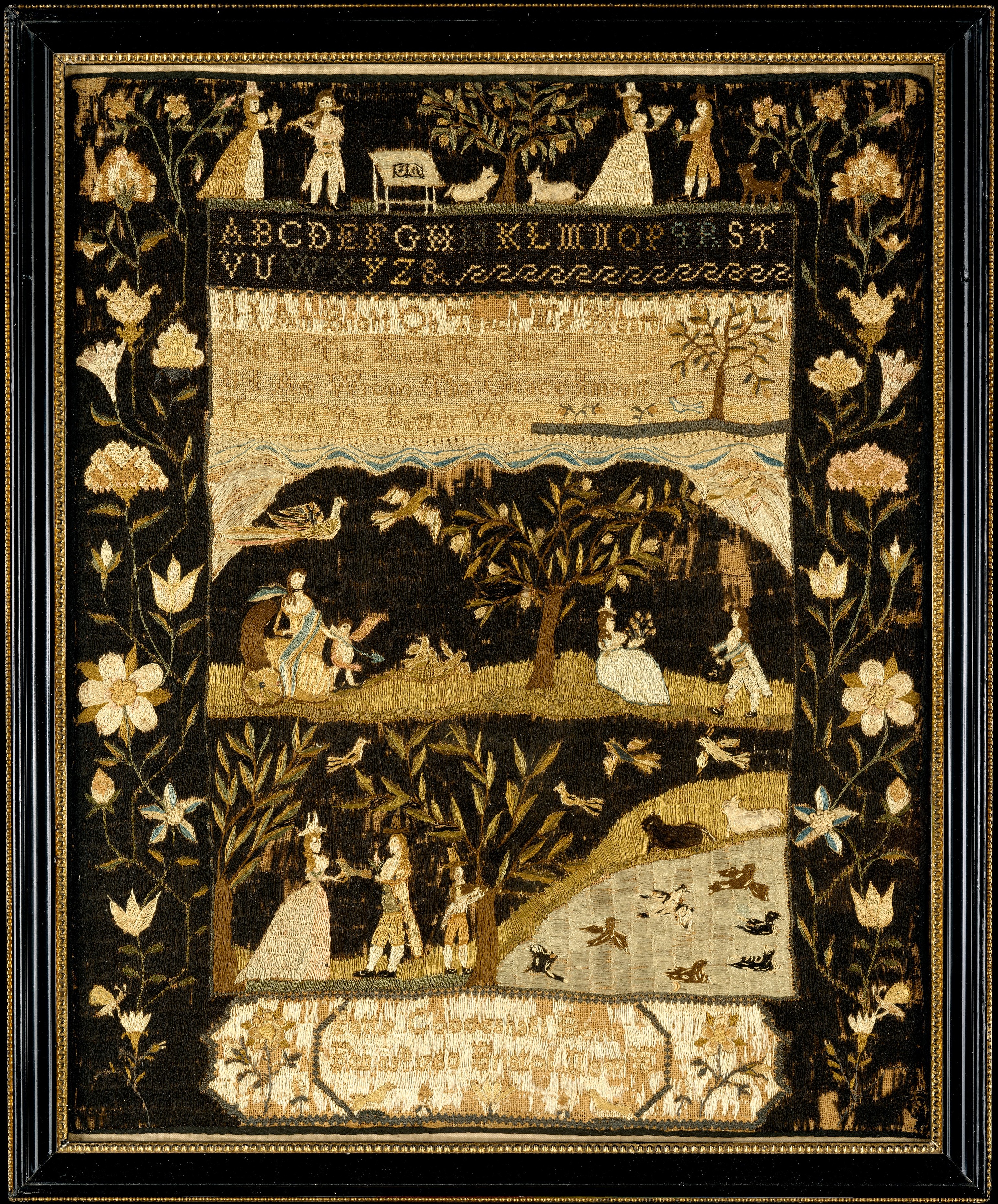

"Sampler" by Martha (Patty) Coggeshall

Mimesis, Expression, Construction: Fredric Jameson’s Seminar on Aesthetic Theory, transcribed and edited by Octavian Esanu. Repeater Books, 2024. 775 pp.

Fredric Jameson, the most influential American Marxist literary and cultural critic since 1960, enters the classroom in black sneakers, trousers with a chain to a pocket watch, and a fitted plaid flannel shirt. A red pen sticks out of the shirt’s chest pocket. On top of the stack of books he carries is a notepad open to that day’s lecture, a vast white space headed by one or two keywords. Graduate and undergraduate students, humanities junior faculty, and curious auditors crowd the room and hallway outside. It’s the start of the 2003 spring semester for Duke’s Literature Department and Jameson is teaching a seminar on Theodore Adorno’s posthumous book Aesthetic Theory (1970).

This stage-setting comes from a transcript of the seminar by the scholar and conceptual artist Octavian Esanu and is presented in a book called Mimesis, Expression, Construction, although its text doesn’t read as a typical collection of academic lectures, but more like a long and busy play.

The challenge of writing about Mimesis, Expression, Construction involves identifying who the book is “for.” Would educated readers who know Jameson’s theoretical work and are curious of his style of pedagogy bounce off its experimental presentation? Would fans of modern literature find it worthwhile to slog through hundreds of pages of literary theory? An exhaustive transcript of a single seminar does seem to offer a snapshot of Jameson’s views on art and aesthetics at a particular moment—after the start of the Iraq War and before the Great Recession of 2008—as well as the nuances of the late critic’s cadence and speaking habits.

After reading one session it’s clear that Jameson spoke in a similar fashion to his writing. A thought is rarely unaccompanied by a parenthetical follow-up: “Architecture is perceived habitually in a state of passive distraction … [Quietly: that is when you’re walking in a building and, unless you’re doing something else, you gotta pay your parking ticket, or something else, you are experiencing the building around you in a passive distractive mode.]” He ventriloquizes the thinkers under discussion: “[Impersonates Adorno] ‘Yeah, yeah, [Brecht] was a great poet, but that’s because he was doing something [Stressing] other than what he thought he was doing…’ [Quietly: this is Adorno’s classic way of dealing with such issues.]” Robert Hullot-Kentor, who furnished the 1997 English translation of Aesthetic Theory, once wrote that Jameson had a “professorial” manner, which evidently applied as much to his lecturing as his theoretical corpus. When he speaks on Heidegger’s later lecturing style, which “no longer has the feeling of philosophical argument,” but is “almost a musical movement in time…. A very special way in which the lecturer, the philosopher, is somehow [Stressing] leading you to the truth in some way,” Jameson is aptly describing his own ideal approach.

According to his introduction, Octavian Esanu’s choice to transcribe these lectures as a play text was inspired by Krapp’s Last Tape by Beckett. It’s an essentially verbatim transcript of his audio recordings of Jameson’s seminar, with nothing left out. Esanu stresses that he searched for a format that would reflect the interplay of the three core “impulses” of Adorno’s aesthetics that make up the title. “Remaining faithful to the innate predisposition of the raw material, and to those aesthetic drives that shape each substance into its immanent form, the project unfolds from the initial effort to imitate Jameson into that of expressing and ultimately (re)constructing a significant academic event and document of modernist aesthetics.” Thus Esanu’s transcription joins the thrust of modernism’s dissonance, aggressive formalism, and conscious state of failure in representation.

A lecture transcript that includes every pause, stutter, filler word, and stray noise makes for a rebarbative reading experience. At one point in the sixth lecture a student whispers, “What part of the chapter is he talking about, what page?” to which another student answers, “I have no idea.” Jameson’s course drew from a wide field of humanities references, and there’s an embarrassment of riches in these lectures in terms of continental thinkers, artists, and designers (Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Freud, Le Corbusier, Heidegger, Thomas and Heinrich Mann). Yet the commitment to this strange presentation—as if Kenneth Goldsmith enrolled in a literary seminar and “transfigured” the semester into one of his books—leads one to read Mimesis, Expression, Construction not as a work of theory but as an “art object,” or piece of conceptual writing. Therefore, the critic shouldn’t interpret and evaluate the object’s execution (all 775 pages of it) but instead the idea that spawned it.

The most interesting element of this book in this light is neither Jameson’s content nor Esanu’s concept, but the obstacles that emerge in the way of the book’s execution. The content of one student’s presentation, on Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” was “significantly reduced” to avoid redundancy, and another presentation was “significantly modified” to avoid “copyright and liability issues.” Certain asides and half-remembered references by Jameson prove impossible to follow up. In addition, there are numerous small errors, inevitable with any transcription project, like Harold “Blum” instead of Bloom, or “across purposes” instead of “at cross purposes,” and so on. The arguable “cross-purposes” of this seminar project—the challenge of reading it, and the commitment demanded by that reading—make Mimesis, Expression, Construction a difficult book to recommend. As a commodity, the tome will set you back by forty bucks. As an art object it will occupy about six centimeters of shelf length.

But with that said, Fredric Jameson’s views on culture, politics, and Marxism continue to animate left-wing discourse in this country (the critic passed away in September 2024, a few months after this book’s publication). The conditions in which Jameson took interest in Adorno’s aesthetics at the turn of the millennium are also significant. A revival of critical interest in Adorno and the Frankfurt School took place in the academic humanities starting in the early 90s. Jameson’s own intervention came in the form of his 1990 monograph on Adorno, Late Marxism.

Jameson’s pivot to Adorno after the first two decades of his career was related to the reorientation in his critical method, from the traditional philosophical debates of idealism vs. materialism to cognitive aesthetics. That is, Jameson’s earlier books like Prison-House of Language (1972), his account of Russian Formalism and Saussurean linguistics, and The Political Unconscious (1981) took on traditional, categorical debates in philosophy, like the fundamental question of thought and being, and which of these two categories comes first. He worked through the theories of Lukács and Althusser’s early period to explore these questions, and made an argument that refrained from taking a side on materialism, or the priority of being. Instead, the “political unconscious” of a given text is in part the repeated staging of this problem. Jameson famously says “always historicize,” but the rub is that history doesn’t exist anymore: it is an immanent effect within the structure of the capitalist mode of production. By the time of Postmodernism (1989), the debate itself has been left behind. Now the emergent sensorium, or cognitive images of “late capitalism,” are the order of the day.

Crucial in this pivot for Jameson was Adorno’s philosophical summation of modernist art, which draws heavily on Kant’s ideas of a priori judgment and autonomous self-legislation, and so on. Jameson has a rap as a principally Hegelian thinker and a promoter of Hegelians such as Lukács, especially in his early period of the 70s. But an intense reading of the ideas he puts forward in Mimesis, Expression, Construction, as I’ll try to show, reveals a relative distance from Hegel and a closeness to the earlier German idealist Kant. The poetry scholar and theorist Robert Kaufman reviewed Late Marxism in 2000, describing it as “Jameson’s effective apology for Adorno’s often apologetic Kantianism.” Indeed, when it comes to their discourse on art and aesthetics, Jameson and Adorno were—to evoke the title of Kaufman’s article—Red Kantians.

Jameson’s own explanation for Adorno’s comeback after decades of obscurity was that times had caught up to his pessimistic critical vision. While Adorno was out of step with the student movements of the 60s, energized as they were by Third World anticolonial struggles, his thinking became relevant again in a period that saw the decisive end of twentieth century socialism, which had taken place in the mid 70s, but was beyond all doubt by the 90s.

A conversation on Adorno with fellow leftists won’t go far before it digs into his glaring flaws and ideological limitations: not to dwell on the point, but it’s no mere coincidence he found “totalitarianism” in jazz and R&B music, two genres with Black American roots. Nevertheless, Adorno’s work has left an impact on leading voices in today’s left intelligentsia when it comes to cultural critique, and his thinking animates some contemporary writers and artists who wish to extend modernism into the twenty-first century. On the other side, the populist and semi-fascist Right continue to pine for a “return” to Beauty, Truth, and Goodness that modernism and the theories of “cultural Marxism” have unjustly expunged. Even critical voices on the left often engage with mass culture, and certainly fine art, with pearl clutching moralism. In short, there is no deficit of narrow-mindedness on either side of the political aisle about the kind of art produced under the social conditions of advanced capitalism—and the sheer speed of art’s production in our bourgeois society won’t slow down anytime soon. With these considerations in mind, it’s worthwhile to clear the ground and make sure we understand the sophisticated theoretical arguments made by Adorno and Jameson.

My journey through this book of lectures became an occasion to sum up Jameson’s way of summating Adorno, and present the thinking of both in a broad, accessible framework. The commentary that follows is organized by the key terms of Adorno’s aesthetics, from Aura to Value. It is a critical exposition in the form of a mini-lexicon; every keyword that has its own section heading will appear in the body text in italics. This way I hope certain relations will emerge, such as how Mimesis and Expression are closer to each other, conceptually, than the two terms are to Construction. While this ground-clearing is meant to be useful for those who want to engage with modern art and cultural critique, the keywords also convey a story of how Adorno’s understanding of modernism succumbed to the same moribund trends of bourgeois culture he was resisting; how Jameson’s analysis of Adorno shifted from a “Hegelian” lens in the 90s to a more accurate Kantian framework; and how these questions of philosophy, art, and society have led us to a dead-end, antithetical to a positive sense of either society or fine art. We start with the problem of how modern art can still have a claim to authority.

AURA

A work of art’s “authenticity, unique presence, and traditional authority” constitutes its aura, according to Adorno’s friend Walter Benjamin. Aura is the articulation of modernist art’s Autonomy, with serial music being a clear example. Twelve-tone compositions liquidated the aura of traditional western music and in the very nature of its pointillistic sound production pushed back on the false universality expressed by the culture industry. The rise of mechanical reproduction and the mass media it facilitates led to the decline of auratic art, of art that gives the viewer a singular moment of experience through its sheer presence. For Benjamin, there was a progressive element to the fall of aura and the rise of Mickey Mouse. Not sharing Benjamin’s confidence in the masses, Adorno saw only increasing rationalization and the social supremacy of exchange Value.

An auratic artwork appears to give more than what’s immediately present in it, while modernist art on the surface spurns aura. Robert Hullot-Kentor is a theoretical critic as well as a translator of Adorno, and he stresses that this attitude is a “negative image,” a shape of what could be different from our actual lived situation, which is also an inverted relation of Mimesis—all of which articulates a dialectical return of aura. This dialectical process is for Hullot-Kentor the core thought of Aesthetic Theory. Mimesis and the Kantian philosophy underlying it, though, still need to be unpacked. But the upshot of modernism’s transmutation of art’s imitative capacity is that it attains what the philosopher J. M. Bernstein calls modernism’s “immanence of form.” That is, the self-rationalization of art, so that it has no purpose other than to be itself, the experience of art’s Autonomy.

AUTONOMY

We are used to thinking about art as no longer subordinate to external religious or partisan imperatives. Art enjoys a freedom relative to its domain, which has been refined and specified across the centuries. But art’s autonomy is also an expression of its disempowerment, or “alienation.” That is, modernist art appears in a historical setting in which art is categorically distinct from truth: it has lost a unity with the truth that it had once enjoyed. With no external truth with which to correspond, the artwork has no choice in this moment of weakness but to reflect on itself. In short, an artwork that is the product of bourgeois high culture and has taken an overtly inward turn may be considered autonomous.

This situation is the latest point in a long history of social development. In the passage from the Middle Ages to modernity, philosophical thought shed its theological garment. Likewise, the fine arts were freed from the religious framework that stringently governed its domain. Now art’s domain is strictly aesthetic.

As manual and intellectual forms of labor split in the development of capitalist production, so too did Beauty from Truth and Right in the ideological sphere. That is, high art doesn’t have anything more to say about philosophy or ethics. Kant—whose system animates modernist and postmodernist aesthetics and thought—established that aesthetic judgment was autonomous, or independent from other types of judgement and anything prior to judgment. What remains is taste. This conceptualization of autonomous judgment developed into a conception of autonomy in art itself. As Bernstein writes, “each modernist work is a differentiated response to the questions ‘What is art?’ and ‘Why is art?’.”

From a certain aesthetic perspective, the growth of art’s autonomy in western culture is a triumphant story in which artists can make art for themselves and likewise people must experience art for themselves. But there are heaps of critical theory concerned with the instability and unsustainability of such conditions. Adorno laid out the stakes for modernist art’s autonomy in the opening line of Aesthetic Theory: “It is self-evident that nothing concerning art is self-evident anymore, not its inner life, not its relation to the world, not even its right to exist.” Art becomes autonomous when it loses its old cultic and social functions, so that, oddly, its purpose now is to have no purpose, to emphatically and repeatedly refuse a purpose. It is forced to reject tradition and search for novelty. Since what is new to art is also not-art, we can say that novelty in art is non-identical. But the quest for the non-identical can never end, since once the new has been incorporated it won’t be new anymore. Art is no longer about making something beautiful that endures, but making something that’s always in a process of emerging. Adorno writes, “Today every work is virtually what Joyce declared Finnegans Wake to be before he published the whole: work in progress.” This inexhaustible search for novelty parallels the rise of capitalist accumulation and bourgeois society’s promise of “undiminished plenitude.”

The more art asserts its autonomy—its self-identity against the world—the more irrelevant it becomes in a rationalized and utilitarian society like our own. And while modernist art strives to make its own rules and thereby create a sense of unity sorely missing in the real world, it can never truly break off its relationship to the shared objective world. As Adorno says, “There is no aesthetic refraction without something being refracted.” Art can heighten itself until its illusions have no practical connection to the world, or it can sell out to the culture industry and “make itself useful,” i.e., generate profit. The autonomy of modernist art is truly a terrible impasse.

For Jameson, autonomy doesn’t replace a connection between the work of art and the social reality that produced it, but specifically points to how art has self-determining, self-contained, and self-sufficient properties. “Cutting beauty off from any practical purpose” was the basis for autonomy in Kant’s Critique of Judgment. Once again, autonomy is seen as the denial of art’s historical sacramental character. And yet Adorno values modernist autonomy as a way to construct texts that contest the status quo via radical formalism. Jameson dwells at length on “The Essay as Form,” a major piece by Adorno, in his seminar. Its title proposes a new type of essay, a meta-essay that “immanently” critiques its content, or critiques without ever withdrawing from the unfolding development of that content. The power of the essay as a form, as Robert Hullot-Kentor understands it, is in how its autonomy is located squarely at the level of artistry, giving it a capacity for self-Mimesis and self-criticism. Jameson argues in his seminar that the essay’s claim to truth may be seen as Utopian. This truth involves the imperative to never forget that art is always a product of labor, a social fact.

The autonomous nature of a modernist artwork is constituted by its tension between Construction and Expression. Experimental technique is the only possible outlet for a modernist artwork’s Aura.

CONSTRUCTION

In the artistic process, the artist dissolves her materials and ideas into a harmonious unity that subordinates both the individuality of her chosen medium as well as her own subjectivity. This process of integration is what Adorno, drawing upon Kantian aesthetics and Benjamin’s ideas on modernism, calls Construction. Modernist artworks push construction’s integrative aspect beyond its own limits, pushing it so far that, according to Bernstein, integration becomes disintegration. The most refined example of a constructivist aesthetic in modernism is the music of Schoenberg.

Opposed to the particularities and contingencies of Mimesis and Expression, Construction is rational, social, and universal. The Autonomy of a modernist work of art is articulated through construction’s tension with Expression, which is effectively the contradiction between form and content. A given work is an arrangement and manipulation of objective materials—paint, words, sounds, etc.—into something that takes on the appearance of meaning graspable by the intellect. But as construction takes the dominant position over expression, there remains, even in Schoenberg, an expressive element, a Mimesis of subjective fear and suffering. The disjunctive, fragmentary experiences proffered by modernist artworks come from the emphatic foregrounding of the presence of construction in the artistic process. Modernism constantly reminds us that art can’t be reduced to Mimesis and Expression alone.

In his lectures, Jameson introduces Construction by relaying an argument from Adorno that says, in Nietzschean language, “even what has become can be true.” That is, an artwork seems to offer a vision of the essential nature of art, but that essence has changed over time, because art’s function in a secular society without magic or rituals can’t be the same as before. In fact, part of art’s Autonomy now is to reject and forget that past. In this view, the fragmentation and outrageous distortions in works like The Waste Land or de Kooning’s Portrait of a Woman (1962) are examples of modernist art rejecting its own vision of art as an illusory well-wrought whole, turning Autonomy against itself. Jameson’s point is that the historicity of art’s function means that what counted and didn’t count as art in a different historical period was different in ways that we can’t access. This is a problem, since we learned that art needs to be related to its other, to the non-identical, to be fully understood. Fortunately, aesthetics is the sphere where this access to historical claims of art can still be found. The historical situation of an artwork’s production has been “sedimented” in the work itself: we can still “make contact” with the “truth of an historical situation.” The location of this contact is not the subject matter but “in the form…or rather what [Adorno] calls ‘technique.’ And this is the [Stressing] constructivism of Adorno.”

Robert Kaufman and Jameson both give insight into how Adorno came to develop his concept of construction. Jameson in his lectures identifies construction and productivity as Adorno’s two main positive categories. “Whenever we have the choice in here [sic]—in this constant back and forth between mimesis and construction, between emotion, expression, and construction—Adorno always seems to come down on the side of construction.” Construction plays a major role in Adorno’s thinking for how to articulate a non-coercive version of enlightenment. (Adorno never wanted to negate or undo the European bourgeois enlightenment, but to complete it.)

“[P]art of Adorno’s interest in developing constructionist ideas,” writes Robert Kaufman, “is to plot an alternative to productionism: not only to capitalist productionism but also to what Adorno regards as Marxism’s own grim version of instrumental rationality.” This line of argument has become the common-sense wisdom of today’s radical liberals. The orthodox Marxist view of organizing the working class into a class for itself, with its own leadership, is dismissed here as a trick to turn the proletariat into objects, identical with the machines and materials they work over but do not possess as a class, in a mindset where organicist-sounding ideas like those of historical materialism are disparaged as unworkable and irrelevant. Constructivism and synthesis are now the only paths to a genuinely recovered organicity. Jameson’s own intellectual career after 2003 would see him move further in the direction of Benjaminian and Deleuzian constructivism.

Like Mimesis, construction seems to be inverted by modernism into disintegration, or to use the technical watchword of modernist art, fragmentation. For Bernstein, fragmentation is the means by which modernism takes its biggest artistic risk, the risk of bringing in the non-identical, the elements that could make the whole edifice fall apart.

To structure a review and commentary on a book of Jameson’s seminar on Adorno’s aesthetics as a mini lexicon advances a similar risk of disintegration. But while key terms break up the argument’s drift, I hope that each term gets enough space to be grasped on its own merits, and that this abstract philosophical material remains accessible both for readers and myself, with the referential format working as a guiderail of sorts. Also, Jameson assigned his students to compose their own indexes for Aesthetic Theory, and it was useful to participate in his “final project” as I read on. But notwithstanding Adorno’s wager that the path to recovering authenticity in culture involves fragmenting via the modernist technique, the result can amount to nothing more than artifice without art, a mere invention. Such artificiality is one of the main properties of Eclecticism.

ECLECTICISM

In a 1993 review article slamming Jameson’s Late Marxism, Robert Hullot-Kentor calls the critic “one of the great tattooed men of our times.” Hullot-Kentor continues: “Every inch of flesh is covered: that web of cat’s cradles coiling up the right calf are Greimas and Levi-Strauss; dripping over the right shoulder, under the sign of the Cimabue Christ—the inverted crucifixion—hangs Derrida.” Jameson’s intellectual project involved ingesting different currents of twentieth century thought, including diametrically opposed trends, and producing an integral if artificial argument to account for the whole. On a practical level, Hullot-Kentor argues, Jameson was a “first-rate list maker.”

Jameson displays his list-making capacity in the second lecture of his seminar, when he discusses the difficulty of pinning down the “theme” of domination, natural and social.

But of course, if you insist on [domination] as the fundamental theme then you turn it into… [Reflects.] I don’t know, not exactly into Foucault but something closer to that… [Cough in the audience.] And I think this is not wished to be that, hmm… [Hesitates.] Maybe it’s a little more like Derrida, for it is something that it’s not wished to be pinned down to a theme.

But to pin down the theme would be to reify the thought into an ideological position. In Jameson’s words, “You have limited Adorno to a certain horizon… .” Of course Adorno and Derrida’s thinking are not unrelated (they were both responding to Husserl), and both Jameson and Adorno made substantial use of both Kant and Hegel. The point is that eclecticism as a style of thought employed by Jameson and his post-Marxist disciples produces work that reads as a mechanical and non-systematic combination of famous names. Jameson, in Hulot-Kentor’s words, “transforms thought into rungs for academic arboreals arcing their way to success making lists of their own.” A kinder critic might say Jameson’s insightful writing serves as raw material for other left critics to make their own analyses and build their own cognitive maps of so-called late capitalism, but this thought overrides philosophy’s command to dare to think in a consistent and rigorous way. “The subordination of thought to the functional order of self-promotion … assures that the gutted, self-evident, and interchangeable results cannot help but shine.” We hear moral appeals in left circles these days to be pluralist and “non-dogmatic,” avoid “class reductionism” and refuse “epistemic violence.” The response I’d deploy is that such pluralism is in fact a residual liberalism that is an obstacle to making the left a serious political presence in the USA again. Mixing and matching ideas, independently of how they developed, is not as radical as it’s cracked up to be. In practice it amounts to Hullot-Kentor’s notion of selecting from a menu of names. “Above each of these names—and now among them Adorno—it reads: ‘Your choice!’”

Jameson described his own project as methodologically eclectic: as we saw above, he gathered trends of thought and theories from twentieth century continental philosophy to orient and articulate his mode of interpretation. His Marxism was always fundamentally informed by Sartre’s “horizons of meaning.” He consciously fused Althusser’s anti-Hegelian thought with figures in the Hegelian tradition like Lukács for his interpretive method in Political Unconscious. Althusser’s work was not only against Hegelianism but aligned with a subjective idealism that Jameson had linked to Kant as early as Prison-House of Language. His Red Kantianism runs back to the beginning of his career.

Ten years later, in Late Marxism he fused Althusser with Adorno, identifying the “constellating” way of thinking and writing done by Adorno and Benjamin as a structure with no center, no “ultimately determining instance,” that is, as Althusser avant la lettre. Hullot-Kentor is right to identify a “need for remoteness” driving Jameson’s analysis. From such a distanced position combining twentieth century intellectual trends, his perspective is like that of a “universal consumer” of methods and discourses, urged on by a fleeting sense of artistic attention before moving along to the next flavor.

In Jameson’s view of what can be achieved in studying Adorno’s work, the only resistance to the trend of pinning down themes involves the kind of formal list-making above, to jump laterally from one “thematic” to the next, leaping constantly amongst these parallel lines, and in such a way that the next one undermines the last, so that the perspective never comes to a rest and thereby advances “an affirmative philosophy.” “Adorno always stays on the abstract plane jumping from one theme to another,” he says, “and the moment you feel like you have something on him, he quickly switches to another idea and theme…” The argument is a useful justification of Autonomy in the field of critical methodology.

During one student presentation, Jameson and the class begin to speculate on the “empty center” of Aesthetic Theory: which key word may best represent the unspoken “middle point” around which Adorno’s text revolves? Is it Mimesis? Tradition? The Sublime? Reconciliation? Revolution? Utopia? We already saw Hullot-Kentor’s constellation of Mimesis and Aura, but of course this query can’t be resolved on the terms Jameson’s course presents. The basic tenet of eclecticism—the orthodoxy of its anti-orthodox posture—is that there is no center, no essential element, and no possibility of understanding things in their totality.

Eclecticism is not unique to Jameson. The intellectual history of so-called Western Marxism consists of its major thinkers “supplementing” Marxism with idealist philosophers: Weber’s theory of rationalization, Simmel on reification, and Nietzsche’s vitalism with Lukács (the best of the bunch); Freudian analysis with the Frankfurt School; Husserlian and Heideggerian phenomenology with Sartre; and Spinoza with Althusser.

EXPRESSION

“In expression,” Adorno writes in Aesthetic Theory, artworks “reveal themselves as the wounds of society; expression is the social ferment of their Autonomous form.” In the secondary literature on Adorno’s aesthetics, expression is closely related to Mimesis, in the sense that what’s expressed in art has an affinity to human suffering. Bernstein glosses expression as the fulfillment of Mimesis in art; in Jameson’s seminar it is viewed as the repressed, modernized version of mimesis. Expression in modernist art gains additional force as these works increasingly close themselves off from communicating any direct meaning or ideological “message,” lest they be instrumentalized by our domination-driven, means-ends society.

By this yardstick, it follows from Adorno’s argument that the most successful political art is not socialist realism as it was employed in the Soviet Union and socialist China, but Picasso’s Guernica (1937), whose tragic expression of anti-war protest finds its outlet in the autonomy of its Construction. The power of modernist art cannot come from saying anything directly about the horrors of capitalism and imperialism, but instead from its decision to sacrifice the techniques that would normally render specimens of the beautiful. No truth about economics, politics, or society, but instead a search for Truth Content beyond beauty, even if the immediate results are “ugly,” in the way Manet’s Olympia (1863), or Joyce’s description of “rancid yellow humour lurking within the softened pulp” of a young woman’s eye, are “ugly.” But the challenges made by modernism to sensibility (through inverted Mimesis and Construction) also lead us further along the red thread of Kantianism as reworked by Adorno.

MIMESIS

Mimesis is the affinity of subject and object as it is felt in one’s knees on seeing someone else stumble on theirs. ROBERT HULLOT-KENTOR

The amount of lore on mimesis recorded in Dialectic of Enlightenment, the secondary literature on Adorno and Benjamin, and Jameson’s work is immense. But in the broadest sense, mimesis speaks to the contradiction of the part and the whole as it relates to human culture. As conscious beings we feel apart from nature, even though we are ultimately a part of nature, and we have a dynamic relationship with nature, both physically (through labor, disasters, etc.) and intellectually. Jameson evokes the old ethnographic example of images or masks that “magically appropriate the forces at work in nature.” This representation is a mimetic adoption of the natural other, and indeed for Jameson, mimesis is a theoretical lens on the subject-object dualism.

In Late Marxism, Jameson famously described Aesthetic Theory’s method as a series of guerilla raids on Kant’s Third Critique. But this image would imply an element of polemic or subterfuge on Adorno’s part. While he was a foe of the neo-Kantians, Adorno earnestly took up Kant’s system to write his summation of modernist art. In this context, mimesis is a cognate of Kantian intuitions and intuitions, at least in Kant’s system, are singular representations that refer directly to their objects: the raw data of sensory input. The mimetic affinity appropriates the likeness of the object in a process that perceives the sensuous particularity of the other, but without dominating the other. The imitation of phenomena in the external world, be they natural or social, the appropriation of their likeness, is a form of primordial sympathy. It’s an act of appropriation by the self of an aspect of the other but is also ultimately a non-egotistical assimilation of the self to the other.

So mimesis endures even in modernist pieces, which are effectively a “rational refuge” for mimesis: the only corner in capitalist society where mimesis still has Value. Rational because mimesis survives, we have seen, by going through the rationalizing process of artistic Construction. Obviously mimesis is now decoupled from any classical notion of beauty, but among Kant’s concepts that are at play, Adorno was least interested in natural beauty or the Sublime. However, sublimity is a salient point in Jameson’s reading of Adorno, and how it changed over time.

SUBLIME

It is easy to imagine something “absolutely great,” in Kant’s words, in the natural world, from Category 5 hurricanes to supermassive stars moving at near-luminary speeds around the black hole in the galaxy’s center. But the absolutely great, strictly speaking, doesn’t occur naturally, otherwise it wouldn’t be beyond comparison. A sublime object has a magnitude of any sort that exceeds the bounds of human imagination and Kantian moral judgment. It surpasses understanding and threatens an end to the knowledge offered by cognitive judgment—all of which is subjectively experienced with a shudder of horror.

But we already learned that aesthetic judgment is restricted to taste: there’s no notion yet about the artist searching for the sublime. Kant, says Jameson early in the seminar,

thought that the business of art was with the beautiful, and that the experience of the sublime was an experience of nature. Adorno then points out that one of the great evolutions in the history of art, beginning with romanticism and going on into modernism, is that now the sublime becomes possible in the work of art.

This locating of the sublime in questions of art and beauty is the basis for saying art has no external criteria, the modernist claim to aesthetic Autonomy. The sublime in art is such because the content of art is framed and set at a safe distance, just as the logic of Kantian judgement puts things at a safe distance.

It’s striking that Jameson had much to say on Kantian sublimity in these lectures and so little in his book Late Marxism. There, the sublime comes up on just one page, and Jameson glosses it as being “reread or rewritten by Adorno” into ontological terms of the encounter with the Other—another one of those “guerilla raids.” Jameson in 1990 was locating Adorno far closer to the Hegelian pole of German idealism, and was “silent,” in Kaufman’s words, on the basic influence of Kantian philosophy for Adorno’s aesthetics. His remarks on the sublime in 2003 read as a follow-up, clarifying the red thread of Kant for both thinkers. Jameson continues with how Adorno extended his concept of the sublime to the whole sphere of modernist art.

The excess of the sublime exists now in modern art’s dissonant, non-representational forms. Jameson says the sublime means art has a “vocation to become a religion or something of that sort…” and modernism is the “hijacking of art, and of beauty in general, by the sublime.” “[I]f modernism has something to do…with the Kantian sublime, then clearly it wants to go to excesses. And if we’re talking about art, then there are only two directions for excess, and this is: everything or nothing.” Either the maximalism of all-inclusiveness, including that which isn’t art, into a “Book of the World”; or a minimalism that elegizes a sensuous life deadened and repressed by our existence under capitalism, one that is even willing to question art’s own Autonomy.

Either way, the modernist sublime generates and releases a shudder of repulsion, which is in fact a latent shudder, a fear of a non-identical natural world, from deep in the cultural past. If Kant’s doctrine of the sublime would sacrifice imagination to the altar of reason, the modernist sublime sacrifices beauty to the altar of truth. (And much of modernist art is given over to grieving for beauty’s death). Adorno’s argument effectively wrestles Kant’s aesthetic judgment out of its silo of taste and lets it play out in the domain of truth and cognition. The conditions that made this move possible came from the appearance of the modernist sublime.

Sublimity is more globally applied in Adorno’s theory of modernism than in those of Michael Fried or Clement Greenberg. But the bigger object for Adorno’s theory is the Truth Content of artworks and art in general, which lives on a higher level than conventional reasoning.

TRUTH CONTENT

Adorno says in Aesthetic Theory that “Truth content cannot be an artefact,” which has a couple implications. One, an artwork’s truth content doesn’t exist in what it represents, and two, if it exists conceptually and not physically, then it requires philosophy or art criticism to unpack it.

As Jameson says, we arrive at truth content only “by doing what [Adorno] calls ‘second reflection.’” Second reflection involves the “right kind of experiencing” of art; this experience is distinct from a direct, “existential” encounter with the work of art. “[There] has to be a slight gap between me listening to this piece of music, or reading this book, and its truth content; it has to be something that I do to this experience…” but not done so systematically that the content becomes reified into ideology. And so criticism is not an excrescence but is necessary both for accessing the truth content and for disrupting identity thinking.

According to Adorno, in the “Draft Introduction” to Aesthetic Theory, “Art awaits its own explanation.” But truth content is central to Adorno’s fundamental part-and-whole perspective. Artworks, like people, are part of the world, but that is not immediate in a modernist painting or sculpture. The historical context of Duchamp’s Large Glass (1915–1923), for example, is compounded into the work, but neither it nor its truth content are perceptible within it, not until a pool of criticism accumulates on the piece, and the Autonomous artwork finds itself embedded in its reception.

But with art whose stance is taken so apart from human society, concerns, and sensibility, what is left to say in aesthetic theory about the human experience? This remainder can only be hinted at in the artwork’s Utopian dimension, which is arguably the most ambiguous keyword of this set.

UTOPIA

In the early nineteenth century, utopian socialists like Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen railed against the impacts of industrial capitalism, and projected a future society based on common labor and ownership, without hierarchy or division. But their agitation for a society without private property remained such—they propagated their moral ideas and schemes for a paradise drawn from thin air and stopped there. They did not grasp the chain of capitalism’s economic evolution, or the evolution of the class struggle to a transfer of political power to organized workers. Marx and Engels initially developed their theory of scientific socialism against utopian socialism.

Utopia has been a dominant keyword for Jameson’s cultural critique since Political Unconscious. Jameson’s commentators are comfortable using the word as a synonym for Communism, but Utopia here is not only a classless society but an aspiration toward a sense of collective interest that is distinct for each existing social class contending in modern society. In Postmodernism, he argues that artworks can make utopian gestures, which compensate for the necessities and wants of existence with aesthetic splendor. The post-impressionist brushstrokes of van Gogh’s picture of A Pair of Shoes (1886), in Jameson’s well-known example, compensate for the “drab peasant object world” by presenting a “new Utopian realm of senses” which foregrounds the oil paint that is the picture’s material, as well as reconstituting “a semi-autonomous space in its own right.”

However, as Bernstein points out, Adorno in Aesthetic Theory is interested in cancelling utopian gestures which claim to transform the work’s subject matter. Van Gogh in this view was not transforming his subject of the peasant object world but transforming the relationship between that world and the practice of painting. “The idea that works that occupy themselves with august events” Adorno writes, “are thereby augmented in their dignity was unmasked once van Gogh painted a stool or a few sunflowers” in a fashion that called attention to his own technique. It’s not the subject matter that is important—in modernist art it’s often trivial—but rather what the artist is doing with it.

The artwork’s authority, its Aura, is in its Construction, not its content. While the forms of modernist art offer nothing immediately reflective of our social existence, this antithetical stance toward society gives art a utopian function: the recognizable suffering that’s given Expression in modernism points to an imagined world without domination, just as our real world is without utopia.

In his seminar, Jameson reads Adorno’s view of utopia as a new relationship between humans and their mortality:

For [Adorno], utopia…is the end of the instinct of self-preservation. It is the instinct of self-preservation that makes for the evil and violence in the world. …Therefore, utopia would be the moment in which the situation is such that you need no longer [sic] exercise this instinct of self-preservation, and the minute when you don’t need to exercise that, then death doesn’t matter.

Communing with art and music, experiencing natural beauty: these activities are forms of “sloughing off the instinct of self-preservation.” If only momentarily, we are free of the anxiety of death and the striving for self-preservation. In Kantian terms, this utopian capacity is an aspect of the artwork’s disinterestedness. The artwork is fundamentally utopian because it is “purposeful without a purpose.” In addition, communing with art has a utopian dimension in which the opposition between subject and object can be momentarily reconciled, like the non-coercive assimilation involved in Mimesis.

This business of championing the particular against domination, resulting in a restorative concept of external nature, is what materialism has come to mean in this framework, after the pivot away from the philosophical line made by Adorno and taken up by Jameson and many post-Marxists afterward. But with this adjustment in the sphere of philosophy come innumerable changes downstream in the sphere of political economy. Now we can see how Adorno’s analysis of modernism fits into a broader account of capitalist society.

VALUE

The material content of a commodity makes up its use value, while the quantity of other use-values it can be exchanged with is its exchange value. The exchangeability of commodities comes from their common property of being products of labor, more precisely, objectified expenditures of abstract human labor, ultimately expressed as exchange value, which is the form of value. A capitalist economy consists of private capital holders, combining labor power with their privately-owned means of production, operating under a general social relation of exchange. The commodity exchange relation is the necessary covering for capitalist production. That is, with no central plan for capitalist production, the only way to figure out what to produce and how much is for producers to compare their products in the market. In this process, qualitatively diverse commodities are “reduced” to quantities of socially-necessary labor.

Gillian Rose incisively argued in The Melancholy Science (1978) that “Reification” as a keyword in sociology and critical theory came precisely from overgeneralizing this thought of the commodity fetish. “The concept of reification in the later neo-Marxist tradition was devised in order to generalize Marx’s theory of value as the model of capitalistic social forms, and to apply it to social institutions and to culture.” Marx’s theoretical analysis of the value relation in Capital metamorphosed into a methodological tool, and the concept of “value” was abstracted from labor input, like how Nietzsche and Foucault and company abstracted “power” from politics, or state power. We have gone from the domain of political economy to a vague epistemological problem: how reliable is our cognition in social conditions as rationalized as our own?

These rationalized social conditions are why modernist art takes an inward turn. An abstract expressionist painting may look irrational in its breakdown of forms and self-sacrifice of Beauty, but that apparent irrationality is a rational reflection of the work’s rationalized conditions of production: and dialectically, by conforming to rationality, the art resists rationalization by serving as an enclave for irrationality.

Adorno’s use of Marxian economic concepts is always-already fused with Max Weber’s analysis of rationalization. The result is a moralistic story of the overtaking of use value by exchange value, leading to a world where everything can be quantitatively measured, and nothing counts unless it commands a price. The predominance of commodity production and exchange in the economy has led to a society hegemonized by identity thinking. If you can say x of A equals y of B, Jameson tells his students, “then we are already in the world of the commodity. Anything that’s exchangeable means that, even though things may not be the same, the act of exchange sets up an identity between them; a sameness has been constructed for them, which has nothing to do with the individual properties.”

A reified society, says Jameson,

is what Adorno calls sometimes “a totally administered society,” a society in which everything is [Stressing] subsumed … [Quietly: and that’s a very important word] under the commodity form. I would then say that, since World War Two, this idea has become the most powerful and widely appreciated picture in the Marxist analysis of capitalism.

This reification—plus the subsuming role of commodity production, it is argued—even surpasses the contradiction between labor and capital. The working class has no special role to play in transforming society anymore.

For the Frankfurt School thinkers, Marxist class analysis was no longer enough in order to have a grip on developments in the twentieth century. Freudian psychoanalysis was enlisted by figures like Erich Fromm to discover a psychological origin of fascism. Nietzsche’s “will to power” was marshaled to complete an apolitical, or rather de-politicized Marx. As Jameson says, “Marxism [Stressing] is not a philosophy of power; it’s a philosophy of production, of labor, of alienation, but not of power… [Quietly: obviously, power is implicit here, but that’s not what Marxism is about. It is economics rather than politics.]” An odd take on a doctrine founded by revolutionaries who participated in the storms of 1848 and supported the Paris Commune. But it is a useful “Marxist” pretext to critique Marxism as an obsolete theory whose principles can be safely abandoned. The context of these revisions occurred alongside interwar debates within the Comintern, as well as the appearance of Marx’s 1844 Manuscripts in 1932. The latter, Richard Wolin writes, were utilized against the “dogmatic” forms of Marxism held by the generation of socialists at the turn of the century. “Instead, Marxism was centrally concerned with problems of human self-realization — with humanity’s 'species being' (Gattungswesen) — that had preoccupied German idealism…” The new portrait of Marx that emerges here is of an environmentally conscious humanist, politically no more radical than a technocratic reformist—that is, a portrait of Marx as the nineteenth century’s Adorno.

In the final session, Jameson locates Adorno’s late work (in the post-war environment, long after the aesthetic debates of the 30s with Benjamin and Brecht) in the context of his struggle in a three-front war: against reactionary postwar thought in West Germany, the orthodoxy of “Stalinist” dialectical materialism associated with “the East,” and mass culture as exemplified by the USA. “And because he was fighting on these multiple fronts, this makes his position look like aestheticizing, or in a defensive posture of supporting a [Stressing] purely art-for-art’s-sake aesthetics, which is often considered bourgeois and incompatible with Marxism.” Still, Adorno may be too interested in production to be an aestheticist, but it takes a lot of scholarly sophistication to argue that his consistent social pessimism is compatible with the Marxist perspective. It is, to use Susan Buck-Morss’s label, “Marx Minus the Proletariat.”

·

But Marxist critique is itself in crisis: there’s no directly practical answer to the questions raised here about the social responsibility of art that wouldn’t be an a priori cop-out. Falling back on reflexive taste and saying “We all like what we like, and that’s enough” is too easy, and obviously didn’t satisfy Adorno either. Copying and pasting a socialist realism from a different place and time is out of the question. Many would call for more modernist art as described here, even if it’s consciously antiquated. But part of the irony of Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory all along is that he composed it precisely at the moment of modernism’s death or suicide, a result of its allergy to ideology and “commitment” and its insistence on self-reflection or nothing. He searched for a justification for art in our society, but his answer set modernist art against society, as a filter of domination’s poisonous symbols and conformity from mass culture, leaving only silence and formal difficulty. The withdrawal of art is the source of its critical edge, its assertion of Autonomy, Aura, and Sublimity (as Adorno defined it), but also of its being outcompeted by the culture industry.

Just as Adorno liquidated the traditional categories and framework of philosophical materialism, Jameson’s reading of Adorno on modernism tends toward liquidating the work of art itself, as if it would be better to kill it before the “deartification” of mass culture, the stripping of Autonomy, is complete. Artworks are the social products of a class society, but modernist art is neither political nor even ideological. It may anticipate Utopian reconciliation in some ways, but this “humanity” of art, Adorno says, “is incompatible with any ideology of service to humankind.” “Orthodox” Marxists believed in an ideological and cognitive role for the fine arts to play in revolutionary societies, despite art’s lack of immediate utility. The radical withdrawal of art in Adorno and Jameson’s story—dissolving both nature and individual subjectivity, while still positing a higher cognitive truth—not only refuses the possibility of transforming society but also leaves the door open for a new religion of art, even if neither thinker took it that far.

Modernism is now at least a century old. Society under advanced capitalism has experienced one hundred-plus years under the tyrannical hold of a reactionary, imperialist, irrationalist culture that is now eroding classical liberalism to maintain the dominance of finance capital. We can’t count on a way out to emerge spontaneously from these conditions. At the end of the day, Adorno’s account of modernism with its negativity and pessimism is yet another expression of an international bourgeoisie in protracted crisis. The first steps in a better direction involve quitting Eclecticism and daring to uncover Marxist theoretical principles that have been diluted and obscured over the decades, to get over our knee-jerk fears of supposedly orthodox thinking. The task of Left critics is precisely to find the new orthodoxy.

However, that search doesn’t have to start far away from Jameson’s method of analysis. As Anna Kornbluh has pointed out, his style of “categorical thinking” and “constructive philosophizing” is an antidote to the dominant trends of empiricism and romanticist navel-gazing in contemporary critical theory. One of the most widely-quoted lines in his most widely-read book, Postmodernism, comes from a passage where Jameson expresses the Marxist dialectic of history in terms of aesthetic estrangement, in the imperative “to think this development positively and negatively all at once; to achieve, in other words, a type of thinking that would be capable of grasping the demonstrably baleful features of capitalism along with its extraordinary and liberating dynamism simultaneously within a single thought, and without attenuating any of the force of either judgment.”

Jameson evokes this dialectic in Hegelian terms early in the seminar transcribed by Esanu. Indeed, he shares the dialectical kernel of Hegel’s idealism in the form of an off-hand joke. He tells the class an anecdote, apocryphal, of Heinrich Heine’s time in Hegel’s lectures. One day Heine asks: “Meister, this thing of yours, ‘the real is the rational and the rational is the real,’ isn’t that sort of a reactionary slogan?” Hegel replies, “To you I will reveal the secret meaning of this saying; it is [that] the real [Stressing] must become rational and the rational must become real.” “And obviously,” Jameson adds, “if you can put it this way, suddenly everything changes.” Everything changes because the first formulation can be read conservatively, to say that established institutions (like the post-Napoleonic Prussian government) are fully justified in their existence somehow. But the new formulation implies that rational things (like a future socialist state) must come into being, and irrational things (like the hampering of productive forces by private ownership) need to be abolished. While it has many faults and artificialities, Jameson’s thinking will continue to contribute to critical discourse after his death. I suggest the best ones to come will not be from his “innovations” or “updates” on Marxism, but where he held fast to socialist and materialist theory, stubbornly and without apology.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC MICRO ESSAY

Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory tr. Robert Hullot-Kentor (1997, 1970); J. M. Bernstein, The Fate of Art: Aesthetic Alienation From Kant to Derrida and Adorno (1992); Susan Buck-Morss, The Origin of Negative Dialectics: Theodore W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, and the Frankfurt Institute (1977); Simon Jarvis, Adorno: A Critical Introduction (1997); Robert Hullot-Kentor, Things Beyond Resemblance: Collected Essays on Theodore W. Adorno (2006); Robert Kaufman, “Red Kant, or The Persistence of the Third Critique in Adorno and Jameson,” Critical Inquiry 26.4 (2000); Robert B. Pippin, Modernism as a Philosophical Problem: On the Dissatisfactions of European High Culture (1991, 1999); Gillian Rose, The Melancholy Science (1978); Fredric Jameson, Late Marxism: Adorno, or, the Persistence of the Dialectic (1990); Richard Wolin, The Frankfurt School Revisited and Other Essays on Politics and Society (2006).

Alex Lanz writes fiction and literary criticism and lives in Brooklyn. He also blogs on Substack at Silent Friends.