ON CHILDREN IN FACTORIES

Carliann Rittman

Self-Administration by J. Arthur Boyle

In a printing factory an hour’s drive from Buenos Aires, children are present.

The factory is called MadyGraf, but it wasn’t always. In August of 2014, the printing factory, which for 22 years had been called R.R. Donnelley, filed for bankruptcy and locked its workers outside. The company was an American one: it began in Chicago in the late 1860s, printed promotional material for Model T Ford in the early 1900s, was the “official printer” of the 1933/34 World’s Fair. Somehow, I guess, it also made MapQuest in 1967. In the ‘90s and 2000s in America the company steadily grew and by the late 2010s was printing the Twilight books and had acquired companies and set up shop in Hong Kong, Canada, and South America. Now, with print, packaging, and supply chain plants all over the world, according to the National Postal Museum, “Every time you collect your mail, you are almost certain to find something that R.R. Donnelley had a hand in putting there."

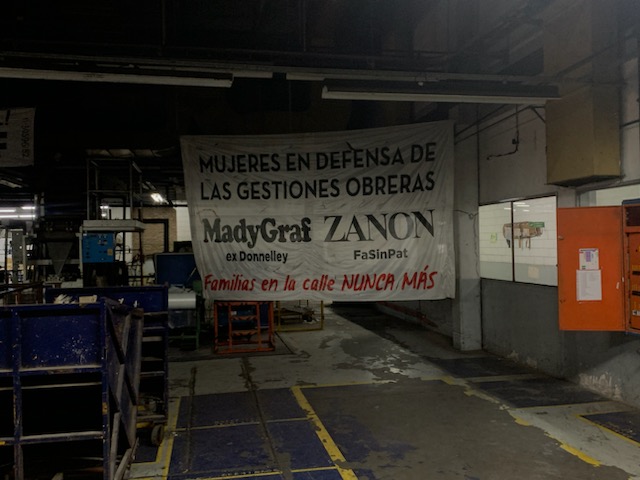

But in 2014, in Argentina, the day after the workers were locked out with nothing but a customer service line to call, they got their hands on some keys, stepped inside the shuttered factory, secured help from college kids to unlock the dormant computers, and ramped production back up. Their takeover wasn’t so much an isolated incident as a long, long road. There was a history of struggle at the factory: years of internal fights against layoffs, and serious power struggles with union bureaucracy. On that day, workers took the shop for their own, renamed it MadyGraf after one of the worker’s daughters, saved jobs, and won full approval of the factory and its machinery’s expropriation from The Buenos Aires Senate. Today, it is very much still up and running.

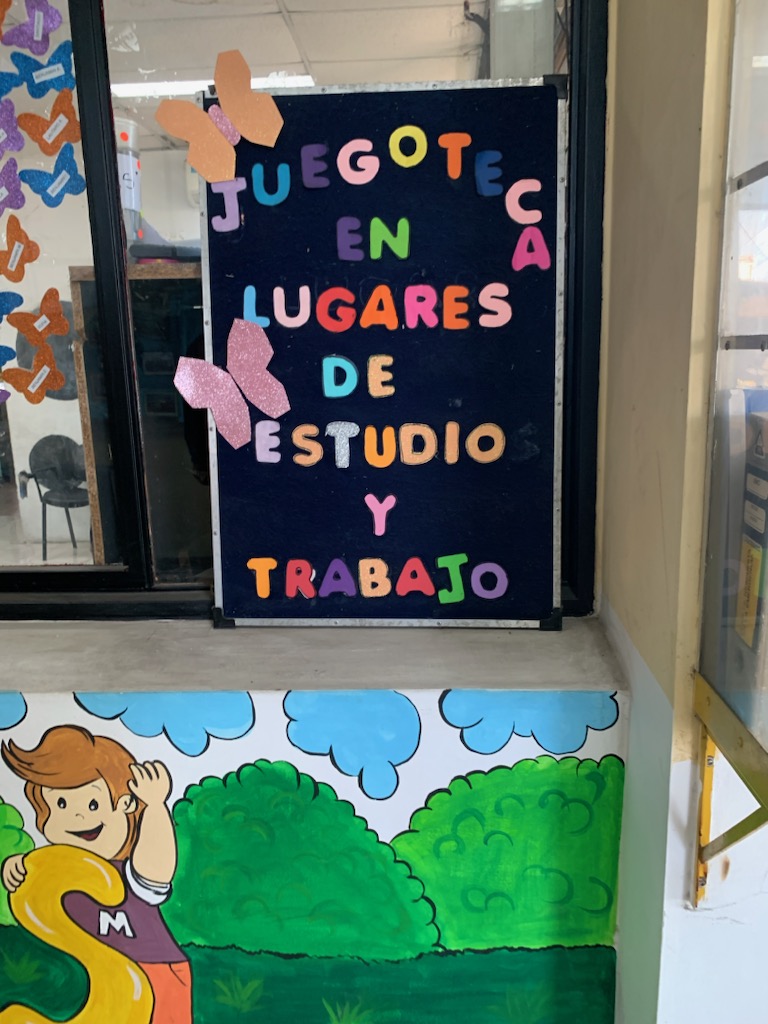

I visited the factory in April of 2024. Inside, the building is marked by change: old turnstiles linger at the entrance, spinning without needing to be unlocked, the loading dock holds no-cops-required concerts, and the former union bureaucrats' office is kind of a storage closet, if that. But before all that: before you see the grand printing machines, before the room filled with pallets of children’s school workbooks, just after the turnstiles, is the room where “bienvenidos” hangs in the window, written in letters round and colorful. Childcare for MadyGraf’s workers, in the room that used to house HR.

That’s an especially exciting shift to me, from the priorities that necessitate a human resources department to a factory where a parent can bring their child, drop them off, know they’re well-looked after, for free, and walk a few more steps to get the job done. Wikipedia describes human resources as “the strategic and coherent approach to the effective and efficient management of people in a company or organization such that they help their business gain a competitive advantage. It is designed to maximize employee performance in service of an employer's strategic objectives.” My eyes spin.

Replacing HR with childcare means in place of ensuring and enforcing employee efficiency in service of their employer is ensuring the workers’ wellbeing in service of a dignified life inside and outside of work. The business still runs, effectively and efficiently and thanks to the workers’ strategic objective (decisions are now made by assembly): customers report improved product quality since the transfer of power. And I know: but how else will you get those anti-sexual assault trainings where you learn how not to say weird things to your coworkers. No, but I know, really: who do you go to if something goes wrong? It’s good to have someone to explain your benefits to you, but I’m happy for childcare to replace human resources. At a traditionally structured workplace, human resources means worker wellbeing through and as far as the company’s priorities. It has to, when the name of the game is the profit of directors or owners.

Here, it’s worker wellbeing as they can make it. Here that makes sense. Sans HR, at MadyGraf I saw serious potential for collective and swift action and adaptability in the name of actually keeping workers well and “effective,” for each other and the world around them: in 2020, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the factory pivoted to produce hand sanitizer and face masks. I saw a room that has each kid’s name on the window written in a butterfly. That, while I was there, was teaching the kids about monochromatic art, with honestly heartwarming children’s examples in purple, pink, and green hanging up. A room that had, hanging in front of some sparkly leaves, a poster that said “La fábrica es del pueblo,” along with one of those draw-a-line-matching-the-term-on-the-left-to-the-definition-on-the-right actives I’ve seen in Bluey activity books, except these ones were defining asamblea, marcha, representantes, and desocupados.

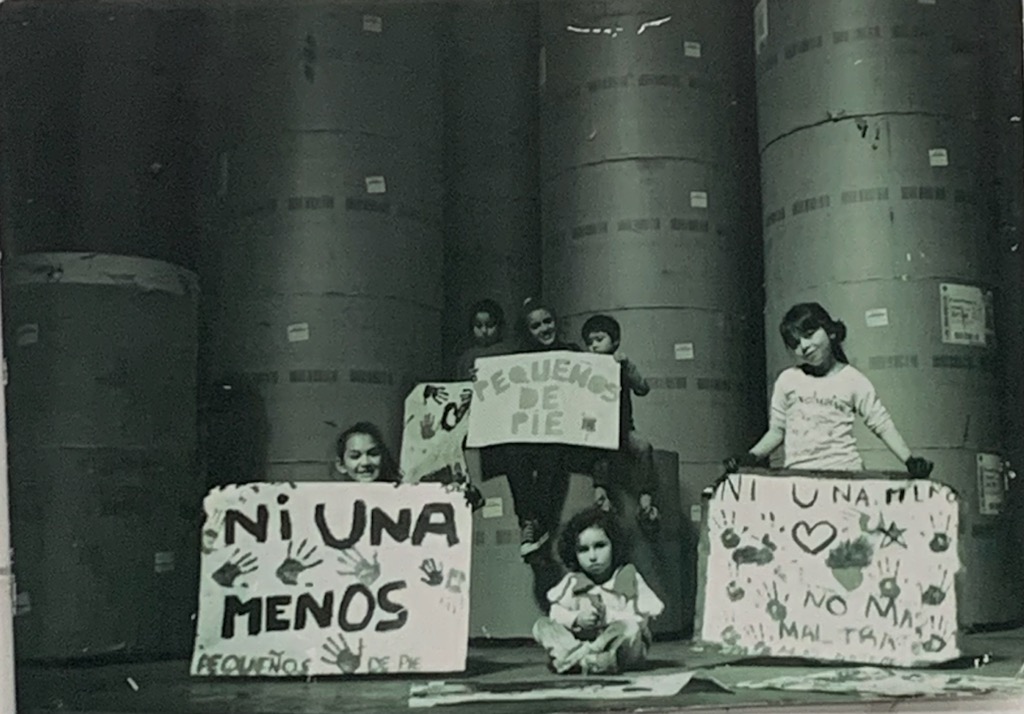

When people complain to me about children being around––which happens, because I’m often talking about children being around––I say something that I bet I read somewhere, which is that where children can be, women can be. I feel this strongly all the time. I felt it walking around MadyGraf, where their women’s coalition includes not just factory workers, but also the workers’ partners. On the wall in the main work room, there's a tacked up glossy photo of children holding a poster that reads NI UNA MENOS. Capitalism claims to care about families, but its failures are apparent. In contrast, at MadyGraf, pictures of workers with their loved ones line the walls. Factories have done such fucked up things to children; they’ve worked kids, they’ve killed kids, they’ve, as Engels noted, led parents to pump kids full of opiates when they couldn't care for them. But at Madygraf, they care for them and teach them.

Here’s Lenin, on créches, a serious system of childcare centers close to or at the places where parents worked: “We say that the emancipation of the workers must be brought about by the workers themselves, and similarly, the emancipation of women workers must be brought about by the women workers themselves. Women workers themselves should see to the development of such institutions; and their activities in this field will lead to a complete change from the position they formerly occupied in capitalist society.”

The dream of the créche is alive. It was the best thing I saw in Buenos Aires.

Carliann Rittman works as a nanny in upstate NY, is a co-editor of the Amenia Free Review, and can be reached at carliannrittman@gmail.com.