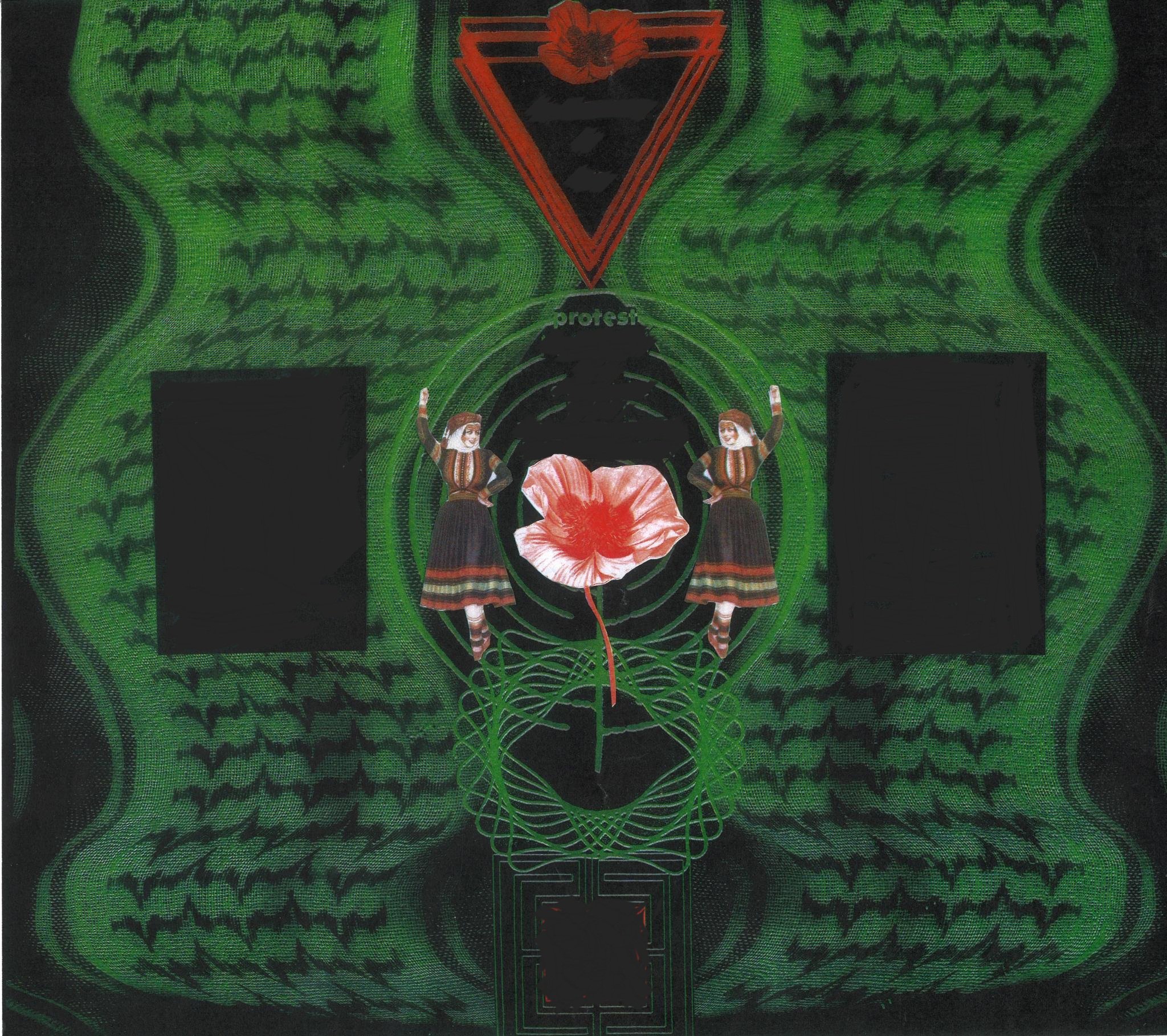

'I Want to Burn the World:'1

On Mohammed El-Kurd's

Perfect Victims

Rosa Martinez

From @atlajala

I met Mohammed El-Kurd once. Well, we didn’t actually meet but, we stood mere feet from one another outside the 2023 Committee to Protect Journalists’ Press Freedom Awards. Neither of us was there to receive said award. Instead, we were among several dozen people who heeded a last-minute call to protest the event, which in his new book, Perfect Victims and the Politics of Appeal, El-Kurd appropriately refers to as the “stenographer party.” Every day, these journalists write dehumanizing news stories and op-eds to shield the genocidal war machine, taking their cues from bureau chiefs who were once intelligence agents. Their words serve as the perfect addendum to Israel and the United States’ bombs, bullets, and missiles. While many of their colleagues are murdered by this same genocidal war machine, the stenographers are paid well and honored at galas.

At the time, mid-November 2023, Israel’s genocide in the Gaza Strip was in its sixth week. Thousands of Palestinian men, women, and children had already been killed, many of them journalists, and the Western media were working tirelessly to manufacture consent for the genocide. False headlines featuring beheaded babies, rape, and human shields abounded, all while Israeli jets incinerated children, Israeli soldiers raped imprisoned Palestinian men, and Mossad headquarters sat in densely populated Tel Aviv. The genocide was, and continues to be, discursively abetted by those from who we seek the truth, journalists.

Perfect Victims, building upon the works of Frantz Fanon and Saidiya Hartman, is an “infiltration of the dominant discourses” amidst the most violent episode in the history of the Palestinian people. The argument El-Kurd makes with equal parts verve, tenacity, and attitude is that the West can never truly look at Palestinians in the eye. To truly look Palestinians in the eye would mean accepting survival and the various forms of resistance taken up by the colonized as the “basic conduct intrinsic to life on Earth.” But to survive, let alone to resist, will always be broadcast as a perverse behavior in newsrooms and headlines, within universities and hardcover books. Yet, this argument is perfectly encapsulated when El-Kurd cites Palestinian poet and activist Rashid Hussein, who asks, “After they have burned my homeland, my friends, and my youth,/how can my poems not turn into guns?”

In the West, granting Palestinian people humanity entails dehumanizing them, defanging them, making sure there are limits in what they say, what they do, and how they react to the slaughter of their families. In turn, the Palestinian subject themself becomes an arena wherein the Western politician, journalist, or academic can reflect and explore what they view as acceptable behavior. In the words of Saidiya Hartman, writing in Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America, this malicious form of recognition functions to “tether, bind, and oppress.” Though El-Kurd reminds us (and perhaps himself) of the futility of words at a time when bunker busters, Merkava tanks, and quadcopters are obliterating hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, the lessons imparted herein remind me of a line from his 2021 poetry collection, Rifqa (named after his grandmother), when he writes, “I am learning how to pour gasoline on discourse.” It is between futility and fire that Perfect Victims stages its intervention.

In further reminiscing on that cold night in Manhattan, El-Kurd recalls making eye contact with several Arab journalists leaving the event, eye contact made amidst chants of “Do your job–tell the truth!” and the handing out of flyers critical of The New York Times’ board of directors. “A few offered me smiles I can only describe as awkward and fled the scene,” he writes. He proceeds to ruminate over why these journalists had been invited—was it on merit? Or, was the stenographer party hiding behind Arabs so as to discount our accusations of racism and Orientalism underlining their coverage of the genocide? Could it be both? Whatever the answer, the lesson to be taken from this vignette, one of dozens in El-Kurd’s masterful and shattering work, is that the institutions robbing the dignity of those who stand in the way of empire are never to be dignified themselves. This vignette stuck out to me, not only due to my being there, but because it brought back the depraved smiles on some of those journalists’ faces, some of them lit up by Nan Goldin’s camera. They weren’t unlike the smiles worn by IOF soldiers as they celebrated blowing up entire city blocks in Gaza or parading around in women's underwear—that same smile of a fascistic glee worn by Oskar Dirlewanger, who murdered 50,000 in response to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.2 Others muttered to themselves while they walked past us, while a select few, the best of the stenographers, literally went out of their way to shove and shout.

How are we to deal with these ghouls? What are we to make of their constant efforts to dehumanize, to “unchild,” to ask questions of us and the wider Palestinian movement that have us fighting an endlessly uphill battle? We must refuse it. We must resist the colonial logic that accuses us of fantasizing about slaughtering Jews en masse (it is, of course, the Zionists who flatten Judaism and Zionism into one identity), or throwing them into the Mediterranean Sea. For El-Kurd, the problem is that we attempt to refute this logic instead of denying their logic any dignity at all. In a particularly striking passage, he writes, “Even if—even if!—my dreams were your worst nightmares, who are you to rob me of my sleep?”

If the enemy does not wish to understand––and it is clear from the last 16 months of vitriol from politicians, university administrators, so-called allies and internet trolls alike that there is zero desire to understand––then no energy should be spent placating them. In fact, as I finish a first draft of this review, one of these genocidal internet trolls is calling El-Kurd (alongside media critic Sana Saeed and Within Our Lifetime’s Nerdeen Kiswani) a “psychopath.” Jeffery A. Sachs––not to be confused with the economist Jeffrey Sachs, whose profile has risen in the last several years while he lectures the world on geopolitics––accuses El-Kurd, Saeed, and Kiswani of “vomiting up their own brand of bile” in regards to describing Hamas’ recent funeral procession for the Bibas family.3 Like many Israeli hostages, the Bibas family were killed by Israeli air bombardment while held in Gaza, and now, as the first phase of the ceasefire ends, they’ve received what countless Palestinians over the last 16 months have been denied: a dignified funeral. El-Kurd laments, “I wish we had the luxury to give our 60 thousand martyrs the funerals they deserved, holding their coffins on our soldiers, instead of being forced to wrap them up in plastic bags and dumping them in mass graves.” According to Sachs, who happily paraded the blood libel of the 40 beheaded babies (with no retraction in sight), El-Kurd is a psychopath for lamenting what his people have been denied. For Sachs, El-Kurd, Kiswani, and Saeed are inconsiderate activists. Sachs' outrage stems from an inability, a refusal, to see anything Hamas and the wider Palestinian resistance does as falling within the bounds of what he deems as acceptable. To him, they are not human, they are masked savages.

Perfect Victims will be engaged with by revolutionaries for years to come. That alone makes El-Kurd’s first work of nonfiction, one still oozing with poetry in every sentence, arguably the most important work of literature of the last 16 months. I say this, not only because I constantly fall victim to aggrandized value judgements but, because there is a breadth to this book that is matched by its readability, its command, and its humor. It is a text that understands that we are, as should be clear to all of us, at a turning point in history. The “rules-based international order” has, in the rawest way possible, proven itself a total sham and never before has “Free Palestine!” rested on the tips of so many tongues. The ceaseless energy activists the world over have poured into this movement should also be utilized to build a revolutionary culture—that is the task at hand. Projects like The New York War Crimes, initially begun as agitprop meant to hold the hosts of the stenographer party accountable for their lies, are a shining example of this. Where social media is drowning in miseryporn (for whom, I don’t know), The New York War Crimes has become a valuable resource for political education. From shining their light on the plight of Palestinian prisoners, to detailing the history of black and Palestinian solidarity, to their latest issues, profiling the healthcare workers who, like the fighters of the resistance, are at the frontlines of the genocide, the New York War Crimes should be imitated and built upon widely. To shatter the colonial logic that leads to the proliferation of the perfect victim narrative, knowledge production must be swift and unabashedly dedicated to the truth. Solidarity is not transactional, but it does require respect and bravery. And for those of us in the West with ample privileges and stages, it is our responsibility to embody a form of solidarity rooted in refusal, resistance, escalation, and higher level of organization.

1 From a poem titled “Abd el-Hadi the Fool,” written by Taha Muhammad Ali, translated by Mohammed El-Kurd.

2 Dirlewanger and his ghouls are famously portrayed in Elem Klimov’s Soviet masterpiece Come and See, a film whose third act is a peek into the carnivalesque hell created by the SS in the Eastern Front.

3 It has been pointed out to me, by Mohammed El-Kurd himself, that the initial publication of this review confused Jeffery Sachs with Jefferey A. Sachs. Though I should say, the former is worth another essay, as his rebranding in the last few years is fascinating, to say the least. Here is a man who is regularly interviewed on Al Jazeera and Democracy Now!, lamenting the excesses of American foreign policy, yet he is the father of neoliberal shock therapy in post-Soviet Russia, an economic transition that led to countless deaths and rampant corruption.